Who do governments represent? The history of voting rights for Brits abroad

By Michaela Benson

It was not until 1985 that the law relating to parliamentary elections in the UK (the Representation of the People Act) was amended to extend the right to vote to UK nationals living overseas. Before this, Britain’s emigrants were unable to vote in parliamentary elections.

This major amendment responded to pressure that had been building over the 1970s to extend the franchise to British citizens living abroad. The original recommendation put forward by the House of Commons’ Home Affairs committee in 1983 had recommended limiting this right to those resident in the countries of the then European Economic Community (now the European Union).

The Representation of the People Act 1985 specified who would qualify as ‘overseas electors’. This included individuals previously having been registered to vote in the UK, limiting this right to those who had been resident (through the provision of a UK address) and thus excluding citizens who had not lived in the UK (with the exception of children who could claim this right through their provision of a parent’s address).

The Act also placed a 5-year time limit on this right. Once they had lived outside of the UK for longer than this, the right to vote in parliamentary elections for Brits abroad would cease on the grounds that ties to the UK would be significantly weakened.

In addition, an annual registration was required to maintain the right.

The parliamentary debate surrounding the Act had concluded that geographically limiting the right to those living in the EEC was unjustifiable, with the result that when it passed into law, the right to vote was extended to British citizens resident anywhere in the world provided they met the other terms.

Importantly, this franchise was limited to parliamentary elections, it was not extended to local elections. The right to vote in European Parliament elections (which the UK has participated in since 1979, when the first European election was held) is independent of this; and while the franchise in the UK includes registered British overseas electors, as EU citizens they may alternatively select to vote in the country of their residence.

Out of sight and out of mind

The right to vote is one of the few issues relating to British citizens living abroad – who are more often out of sight and out of mind for parliamentarians – that ever finds its way into the Houses of Parliament.

Since 1985 there have been further amendments, first extending the franchise of overseas electors to 20 years, in 1989. Then, through amendments to the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000, the qualifying period for Britain’s emigrants was reduced to 15 years in 2002 under the Labour Government.

The Conservative manifestos for 2015 and 2017 included a commitment to extend the franchise of overseas electors to a vote for life. Despite the commitment, this was introduced in the last parliamentary session through a Private Members Bill (the Overseas Electors’ Bill 2017-19), which is supported by a group of MPs, rather than a Public Bill, which is brought forward by a government minister. The bill failed to complete its passage before the end of the parliamentary session. This means it will make no further progress.

The debates which accompany these parliamentary processes, and the changes they have (and haven’t) introduced, centre on the question of whether these UK nationals should have a say in the future of a country in which they no longer live. In many ways, they appear to question their allegiance to the United Kingdom offering important insights into who ‘the people’ are that the British parliament believe they represent.

Growing number of registrations

Until 2015, the numbers of overseas electors registered to vote had never exceeded 35,000. These low numbers might suggest that there is limited appetite among British citizens living overseas to vote in parliamentary elections. However, there are other factors that explain this.

Particularly notable are the challenges prior to the introduction of online registration and the fact that there is no dedicated representation for overseas electors. The latter is especially surprising considering that the UK has one of the highest emigration rates in the world. This rate is further remarkable in being consistent historically. Even back in 1985, when overseas electors were originally enfranchised, it was estimated that 1 in 15 British citizens lived overseas.

In the run up to the Brexit referendum, the number of overseas electors registered to vote jumped to a record high of 264,000. This was likely spurred by their interest in the outcome of the referendum, but also by the introduction of the electronic system for registration.

My conversations with UK nationals living in the EU27 for the Brexit Brits Abroad research also reveal that it was at this stage that a lot of overseas Britons discovered that they had been disenfranchised by the so-called 15-year rule.

The registration of overseas electors continued to climb. By the time of the general election in 2017, it had risen to 285,000. And while we do not have the numbers at present, it is likely that overseas voter registrations have continued to climb in anticipation of general election 2019 and the possibility of a second referendum.

So where are we now in respect to the right to vote of Britain’s emigrant population? Some answers may come from the manifestos of the three major political parties in the UK.

The Conservative Party, who have historically been at the forefront of campaigns to enfranchise the UK’s emigrants, include in their manifesto a pledge to remove the time limitations on the qualifying period for overseas electors. This would mean that people would maintain their right to vote for life. Of course, this was precisely the promise made in their manifestos for general election 2015 and 2017, with the related legislation failing to pass within the parliamentary term.

The Labour Party do not address this at all in their manifesto for general election 2019, despite promising to extend franchise to all those resident in the UK (irrespective of citizenship) and to reduce the age at which people can vote. This is perhaps unsurprising given the parties systematic objection to changes to the franchise of overseas electors in recent parliamentary debates.

The Liberal Democrats include an explicit pledge to extend the franchise to a vote for life, to establish overseas constituencies with dedicated members of parliament, and to ensure that overseas electors can vote in referenda.

Two contrasting examples

How does this relate to the voting rights of other EU citizens living outside their country of nationality? There are a range of practices in different countries. Talking about voting rights with British citizens living in France, the example that they often present is France, which upholds a lifelong right to vote for its citizens who enjoy dedicated political representation.

But Britain’s other neighbour, Ireland, restrict their voting rights to those who are resident. In other words, with a few exceptions, those leaving Ireland lose the right to vote.

What these two contrasting examples show is that citizenship per se does not equate to a right to vote. But at the same time, it does point to the question of who governments believe they represent. And, from a sociological perspective, how they understand who counts as British.

Michaela Benson

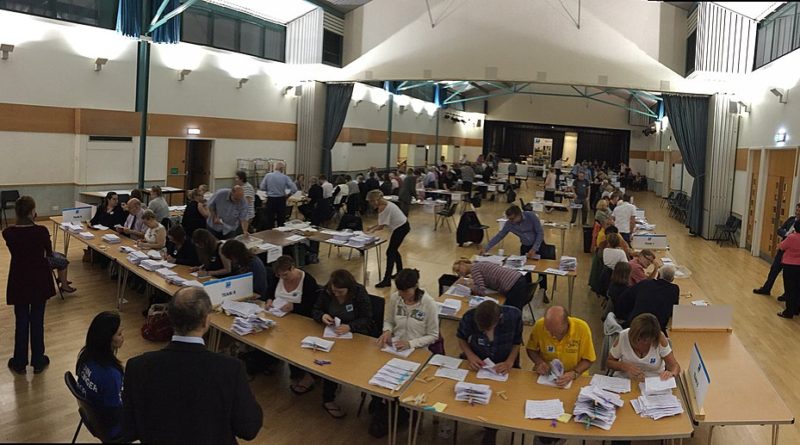

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Michaela Benson is a Reader in Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London, and the research lead for the project “BrExpats: Freedom of Movement, Citizenship, and Brexit in the Lives of Britons Resident in the EU-27,” under the UK in a Changing Europe initiative.