Citizens’ rights and EU trade agreements: where is the best match?

Possible trade arrangements between the UK and the EU have been discussed at length since the EU referendum. Little has been said however about the place citizens’ rights will have in the new EU-UK relation. In this area the focus is usually on residence. But other rights derive from EU membership and many are not guaranteed under trade agreements. What are the options available for the future?

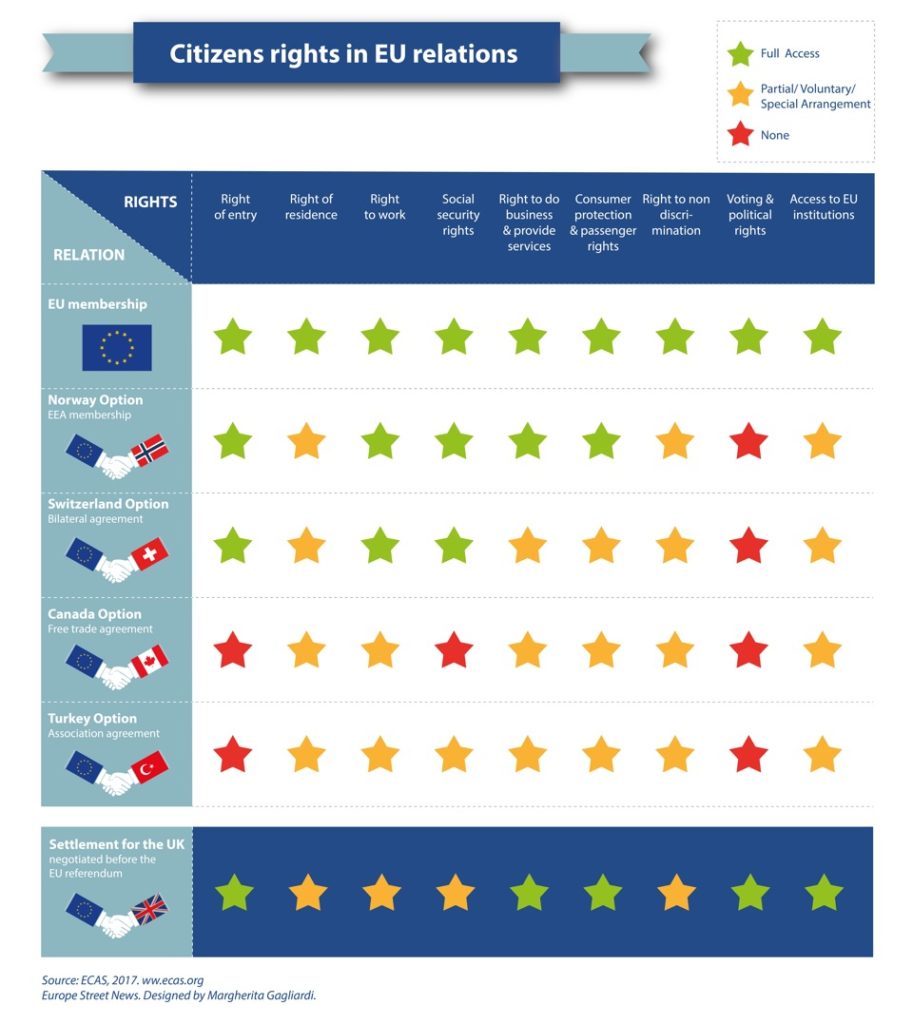

The European Citizen Action Service (ECAS), a non-profit organisation in Brussels, has thrown some light on the matter comparing different scenarios. Together with the EU Rights Clinic, the European Disability Forum and New Europeans, they have compared citizens’ rights in the EU with those available to members of the European Economic Area (EEA), e.g. Norway. They also considered conditions included in the EU bilateral agreement with Switzerland, the free trade agreement with Canada and the association agreement with Turkey.

The report concludes that, EU membership excluded, the best possible deal for people is within the EEA. In this scenario, Brits would retain most of the EU rights, except for voting and political participation.

The Swiss model adds limits to permanent residence, freedom of establishment, provision of services, non-discrimination and consumer protection.

Although they partly restrict EU rights, the Norwegian and Swiss options still imply that the UK would accept free movement of people from the EU, one of the stated red lines of the British government. So these options are unlikely to be considered in Brexit negotiatons.

The next choice would be a free trade agreement similar to the one signed by the EU with Canada (CETA). Free movement of persons and freedom of establishment do not apply in this case, but temporary migration for employment or self-employment is possible. Canadian citizens who visit the Schengen area for up to 90 days do not need a visa and both Canadian and EU citizens enjoy some rights to equal treatment.

Turkey’s association agreement also excludes free movement of people. Unlike Canadians, however, Turkish citizens need a visa to enter the EU (negotiations are ongoing to relax this policy). Turkish workers in EU countries can gradually accumulate residence rights and, like other third country nationals, can benefit from the coordination of social security in the European Union.

The final option, the “hardest version of Brexit”, implies a no deal. In this case the relation between the UK and the EU will be managed under World Trade Organisation rules, which do not confer any right to citizens to enter, reside or work in other countries.

“With this report we wanted to show different scenarios currently available for EU citizens’ rights. There might be others. The conclusion is that there is no best alternative to EU membership under which all rights EU citizens in the UK and UK citizens in the EU currently enjoy can be guaranteed, at least to the same level as they are today,” said ECAS Outreach Manager Marta Pont.

“Voting and political rights are lost in all scenarios. The right of entry, the right to reside, the right to work, social security rights, the right to do business and the right to non-discrimination could be at risk, depending on the scenario. A choice will therefore have to be made as to which ones should be preserved.”

The report also considered the “new settlement for the UK” negotiated with the European Union by former Prime Minister David Cameron before the EU referendum. This would have meant remaining in the EU under a special status. The UK would have been able to invoke an “emergency brake”, limit benefits for newly arrived EU workers for a period of four years, limit child benefits claimed by EU workers whose children are resident in another EU country and apply more stringent national rules to non-EU spouses. The agreement would have effectively allowed partial discrimination between EU and UK nationals, but it was scrapped as a result of the EU referendum.

Citizens’ rights (based on ECAS report)

Right of entry (no visa). Fully secured with EU membership and under the Norway and Switzerland models. Neither Canada’s free trade agreement nor Turkey’s association agreement provide for the free movement of persons, so the right of entry of EU citizens into these countries is subject to their immigration laws – and vice versa.

Right of residence. Fully enjoyed in EU countries. In Norway and Switzerland the right is guaranteed under particular circumstances. EU migration rules apply to Canada and Turkey: citizens of third countries who are highly-skilled, seasonal workers, workers in intra-corporate assignments, people involved in research, studies, pupil exchanges, unremunerated training or voluntary service can benefit of residence rights.

Right to work. Norway and Switzerland have free movement arrangements similar to the EU. Neither Canada’s nor Turkey’s agreements guarantee a general right to work to EU citizens and vice versa. However, Canada’s free trade agreement seeks to facilitate the exchange of high level professionals on a temporary basis. Turkish workers start accumulating working rights in the EU after being legally employed in a EU country for a year.

Social security rights. Norway and Switzerland apply EU rules on the coordination of social security (e.g. pensions). This extends to Turkish workers in the EU, but EU citizens living in Turkey do not fully benefit of the same rules. Canada’s free trade agreement does not involve coordination of social security at EU level.

Right to do business and provide services. Guaranteed in the European Economic Area (EU plus Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein). Swiss companies cannot freely set up business in the EU – and vice versa – but individuals can establish themselves in Switzerland as self-employed. Canada’s free trade agreement allows cross-border trade in services by companies and individuals, excluding some sensitive sectors. Turkey’s agreement contains provisions on the right to do business, but they are yet to be applied.

Consumer and passenger rights. These involve, for example, guarantees and returns for goods or compensation and assistance for travel delays. Fully secured throughout the European Economic Area, they apply to anyone buying goods or services in the EU or starting their journey within the EEA territory, regardless of their nationality. Switzerland complies voluntarily with some EU rules on consumer protection and fully applies EU air passenger rights. Canadian companies wishing to supply services and goods in the EU (and vice versa) have to comply with the respective consumer rules, but Canada is not bound by EU passengers directives. In these areas Turkey is aligning its provisions to those of the EU.

Right to non-discrimination. Aiming to forbid discrimination, e.g. for recruitment, on the grounds of nationality, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation, these rules are fully guaranteed only through EU membership. Under all other scenarios there are some reciprocal arrangements that prohibit discrimination on nationality grounds but EU legal instruments do not apply.

Voting and political rights. These include the right to stand and vote in the European parliament election and in local elections, to seek consular protection from another EU country abroad and to participate in a European Citizens’ Initiative (an invitation to the European Commission to legislate on a matter of interest, supported by a million signatures). Such rights are only granted as part of the EU membership as they derive from EU citizenship.

Access to EU institutions. Every person residing in a EU country can petition the European parliament, submit complaints to the European Commission, request access to EU documents or, in cases of maladministration by EU institutions, complain to the European Ombudsman. EU citizens residing in Switzerland, Canada or Turkey do not have any right of correspondence with national institutions.

Claudia Delpero © all rights reserved.

Photo courtesy Pixabay.