Brits bound to lose their rights in Europe under new trade deal

In negotiating the UK exit from the European Union, the British government promised to “take back control” of borders and end free movement of people from the EU. This also means that, unless they hold a second passport from an EU country, 65 million Brits will also lose their free movement rights in the EU. Under which conditions will they be able to live, study and work in Europe in the future?

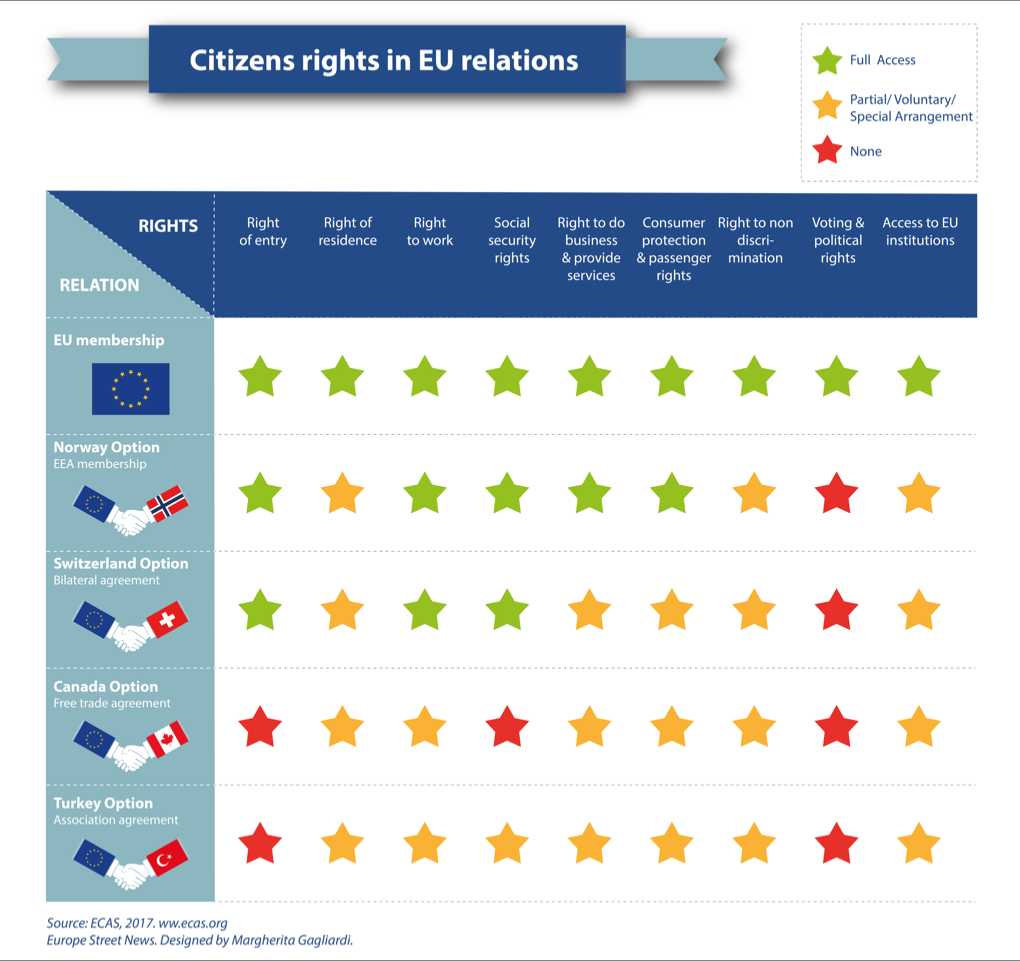

European Citizen Action Service (ECAS), a civil rights group in Brussels, compared different EU trade agreements to understand the options. It found that EU membership is the only way to keep all existing rights.

What is free movement

Free movement of people is one of the four “freedoms” at the core of the EU project, together with free movement of goods, services and capitals. It involves a bundle of rights allowing people from EU countries to live, study and work in another EU member state without obstacles or discriminations. The right of entry and residence, the right to study, work and do business, the recognition of professional qualifications, as well the right to access and export healthcare and social benefits (e.g. pensions) are included. EU citizens living in other EU countries also have political rights, such as voting in municipal and European elections. They can petition EU institutions and, when outside the EU, they can receive consular protection from other EU embassies if the home state is not represented.

Only some of these rights are applicable in EU trade agreements.

The European Economic Area

EU membership excluded, ECAS found that the best option for citizens’ rights is within the European Economic Area (EEA) – the “Norway option”. In this scenario, Brits would retain most free movement rights, except for political ones as these are associated to EU citizenship. EEA states (EU members plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway) can only decide unilaterally to limit the right of residence in case of “serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties liable to persist”.

The EU-Switzerland agreement

The EU-Switzerland trade agreement includes free movement of people, but there are some constraints. As the EU citizenship directive is not incorporated in the Swiss deal, there is no right of permanent residence after 5 years. Also, in Switzerland non-EU family members of EU nationals need a visa. There is coordination of social security benefits, but the right to work can be restricted in public services that involve the exercise of public power. Swiss companies are not allowed to freely establish themselves in the EU and vice versa unless there is a sectoral agreement (it is the case for insurance, air, road and rail transport). There is no general agreement on free movement of services either. However, individuals can establish themselves in Switzerland on a self-employed basis or provide services to customers residing there.

Norway and Switzerland are also part of the Schengen area, which allows residents to travel without border controls.

The EU-Canada agreement

Another option is based on the EU-Canada trade agreement (CETA). Free movement of people and freedom of establishment do not apply in this case. Canadian citizens who enter the Schengen area and stay for up to 90 days do not need a visa and both Canadian and EU citizens enjoy some rights to equal treatment when it comes to employment. Migration for employment or self-employment is possible, as long as it is for a limited period of time (one to three years depending on the activity). The agreement explicitly states that it does not cover job-seekers, employment or residence on a permanent basis. CETA provides a general framework for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications, but does not contain rules on the coordination of social security. Cross-border services by companies and individuals are allowed, except in sectors that are considered sensitive.

The EU-Turkey agreement

Finally, there are Association Agreements, similar to the one between the EU and Turkey. This also excludes free movement of people. Turkish citizens need a visa to enter the EU and, with regard to residence, they have to abide by the immigration rules of the country where they seek to relocate. Turkish workers who are legally employed in an EU country for at least a year can start accumulate residence rights, although social security coordination is yet to be implemented. Establishing a business or providing services in EU countries (or vice versa) also depends on national laws. The Association Agreement prohibits discrimination on the grounds of nationality, and provides for equality of treatment between Turkish nationals and EU citizens as regards conditions of work.

No agreement?

But what will happen in case of “no deal”? Brits who intend to move to an EU country would be covered by the EU directive on the status of non-EU nationals. This is not enforced in Ireland, Denmark and, currently, the UK. While domestic immigration laws apply, citizens of third countries living legally in an EU state for at least 5 years can obtain long-term resident status. This ensures equal treatment with the country’s citizens in areas such as employment, education, social security, taxation and freedom of association. Long-term residents can move to live, work or study in another EU country under certain conditions, and be accompanied by their family members.

There are also provisions securing the rights of third country nationals if they are family members of EU citizens. And access to EU institutions can be exercised by anyone residing in the EU.

Bespoke deal

It is possible that rather than following existing trade agreements, the EU and the UK will define a new form of cooperation. But the recognition of rights of people moving across their territories will always work on a reciprocal basis.

British citizens leaving in another EU country before Brexit will be covered by the withdrawal agreement which is currently under negotiation.

Claudia Delpero © all rights reserved.

Photo courtesy Pixabay.