Cross-border healthcare needs improvement: EU watchdog

EU citizens can buy medicines and plan medical treatments in other countries of the European Union, and receive the reimbursement they are entitled to where they reside, under the EU cross-border healthcare directive. But the system is still not working properly and many people are not aware of their options, according to an assessment by the European Court of Auditors.

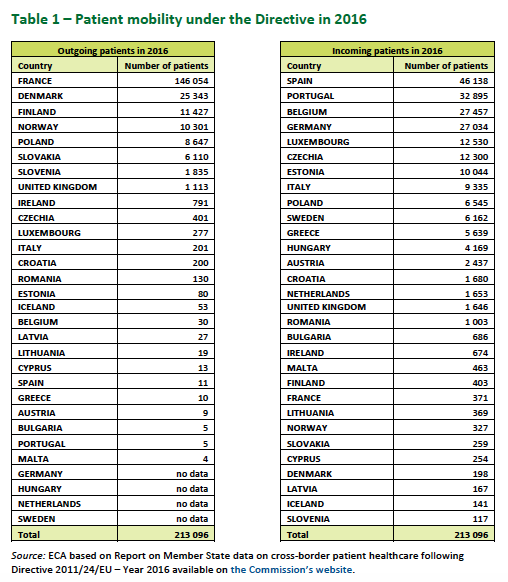

Only 200,000 EU patients a year (less than 0.05% of the EU population) receive pre-arranged healthcare from other countries of the European Union. The majority of cases involve neighbouring states. France is the country with the highest number of people seeking healthcare elsewhere, followed by Denmark and Finland. Spain, Portugal, Belgium and Germany receive the majority of patients from other EU countries.

Healthcare is a national competence and the EU directive does not encourage patients to go abroad to be treated. It recognizes, however, that in some situations the most appropriate care might be available away from home. In such cases, it says, patients have the right to receive “safe and high-quality care” and to be reimbursed according to the system of affiliation. The directive also specifies that certain types of care require previous authorization, with specific rules set in each country.

Eight years after these measures were put in place, EU auditors, the ‘guardians’ of EU finances, looked at how the system works. Their report says that “only a minority of potential patients are aware of their rights to seek medical care abroad”. They also found “problems and delays” in the electronic exchange of patients data between EU countries, which should facilitate treatment across borders.

“EU citizens still don’t benefit enough from the ambitious actions set out in the cross-border healthcare directive,” said Janusz Wojciechowski, the auditor responsible for the report.

Delays on EU data sharing

Under the directive, the European Commission established National Contact Points to inform patients about their rights, the standards of treatment abroad, reimbursement rules and other legal issues.

The Commission is also building a voluntary eHealth Digital Service Infrastructure (eHDSI) for the electronic exchange of patients’ data across EU countries. This is “particularly relevant for countries with a large diaspora,” the Commission said.

But according to the auditors, the Commission has “underestimated the difficulties” of putting in place such an infrastructure. Some countries (e.g. Denmark) are not participating. In some others, the use of electronic prescriptions is limited (the only exchange of ePrescriptions in Europe is between Finland and Estonia). And data protection is an additional challenge.

“High added value” for rare diseases

One of the fields in which the directive was meant to be especially valuable is the treatment of rare diseases. It is estimated that 6,000 to 8,000 rare diseases affect between 6 and 8% of the EU population, or between 27 and 36 million people. The limited number of patients and the scarcity of knowledge on some of these conditions make the cooperation at the EU level “of very high added value”, notes the report.

In this regard, the EU Commission set up 24 European Reference Networks (ERNs) to share knowledge and provide virtual consultations. By the end of 2018, 952 healthcare providers in over 300 hospitals were taking part, with patients organisations, doctors and healthcare providers “widely supporting” this approach.

EU auditors, however, noted that these face “significant challenges to ensure they are financially sustainable and able to operate effectively across national healthcare systems.”

Information and trust

EU auditors have recommended the European Commission to improve the management of the system and provide more support to the National Contact Points and the European Reference Networks. But trust of EU citizens also remains to be won.

A 2018 survey by ANEC, a European consumer organisation, showed that only 4% of over 1,600 respondents had travelled abroad for planned healthcare and only 25% were aware of the National Contact Points. Even when they knew about this opportunity, people were reluctant to seize it.

A majority were concerned about redress if things went wrong (57%). Significant portions did not trust the quality of the service they might receive or were satisfied with their own system. Many also said they could not afford the travel costs.

Planned cross-border healthcare is different to the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC), which ensures that EU citizens are treated if they have accidents or illnesses during temporary stays in other EU countries. According to the European Commission, almost half of the EU population has a European Health Insurance Card and approximately 2 million claims are made each year by people using it.

Claudia Delpero © all rights reserved.

Photo by Peter Kohalmi © European Union 2013 – Source EP.