What happens to Brits when EU free movement ends

There is a lot of talk in the UK about ending free movement rights for people from the European Union after the country leaves the bloc. But there is little discussion about the reciprocal loss of rights for British citizens who intend to move and live in the EU post-Brexit.

Negotiations between the EU and the UK have so far focused on the status of EU nationals already based in Britain and of Britons living in the EU. The EU wants to guarantee the rights of the latter group only in the country where they reside, not the possibility of ongoing movement to other EU states. Whether this restriction will remain in place is yet to be seen. But some 60 million Brits who live in the UK will completely lose their free movement rights in the 27 EU states if the government puts an end to free movement for EU nationals.

So what are the options for British citizens who want to move and live in an EU country after Brexit? A presentation of existing laws and cooperation models published by the European Commission outlines some of the scenarios.

The single market option

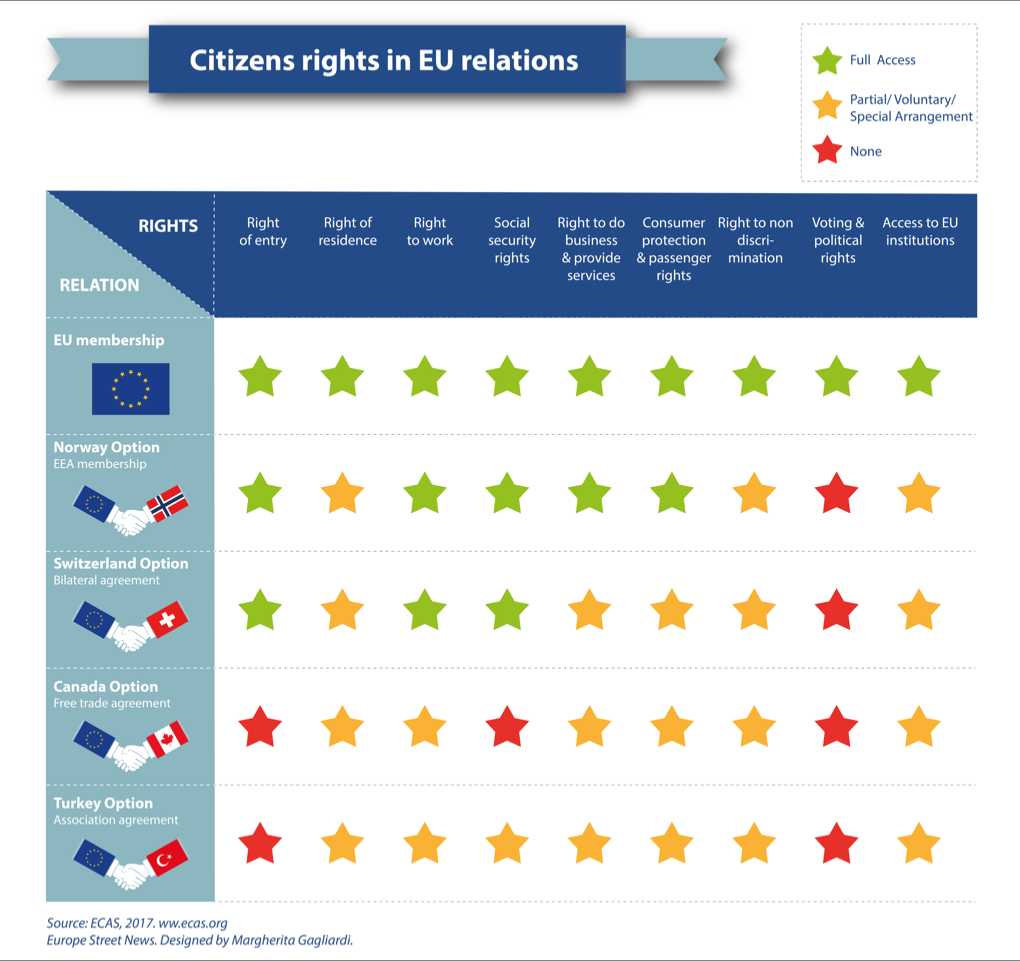

The most complete set of rights outside the EU is provided to members of the European Economic Area, which includes EU states plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. Workers, students, self-employed and self-sufficient people would be able to establish themselves in other EEA countries as they do now. This, however, would require maintaining free movement rules and the arbitration of the European Court of Justice.

This option, however, would curtail the political rights derived from EU citizenship, i.e. the right to vote in local elections in the country of residence, the right to elect members of the European parliament, the right to receive consular assistance from another EU state in a third country and the right to launch and support European Citizen Initiatives (mass petitions asking the EU to legislate on a matter of interest). Regardless of future agreements, the European Commission has already said that British citizens will lose the rights related to EU citizenship on Brexit day, 29 March 2019, and these will not continue during the transition period.

Graph based on a report by European Citizen Action Service (ECAS), 2017. Europe Street News.

‘Third country nationals’ directives

Outside the EEA framework, and unless there is another agreement, after 29 March 2019 British citizens will become ‘third country nationals’. EU rules for third country nationals apply irrespective of whether they are reciprocated in the country of origin, but the legal framework for this scenario is more complex (the UK, as well as Ireland and Denmark, had opted out from such rules).

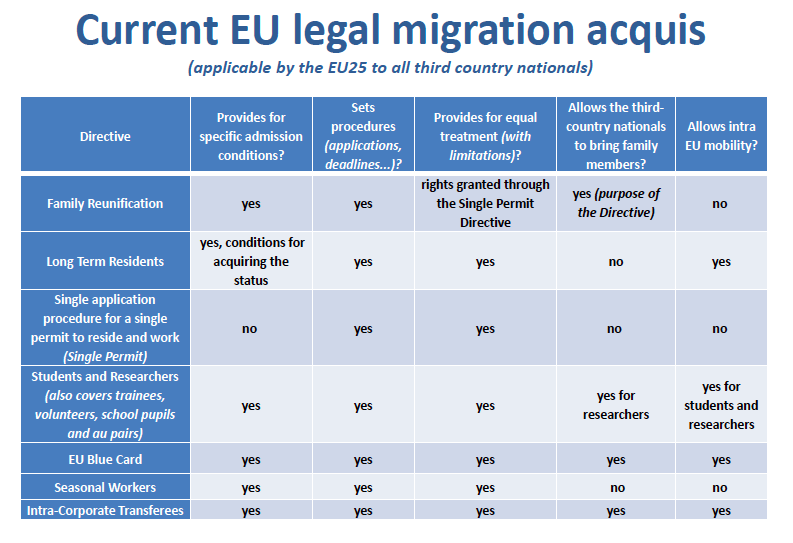

A series of different directives apply to non-EU citizens depending on whether they are workers, students and researchers, highly skilled professionals, seasonal workers, intra-corporate transferees or family members. Each directive provides a different set of rights. Other groups not covered by EU rules (self-employed, low and medium skilled workers, jobseekers, retired or self-sufficient persons) would depend on the national framework of the host country.

An important aspect that is not necessarily covered in this case is social security coordination. Each EU country sets the conditions to get social security benefits and EU rules apply when at least two EU states are involved. So, for example, pension contributions could be accumulated across countries if a non-EU citizen has worked in different EU states, but not necessarily with those of the country of origin.

Third country nationals can become long-term residents after having lived legally in an EU state for an uninterrupted period of five years. As long-term residents, they then benefit of similar rights of EU nationals, except those derived from EU citizenship.

These rules do not cover ‘service providers’, e.g. self-employed, business persons and professional categories such architects, lawyers, chefs and fashion models. In the absence of another type of deal, such groups would be covered by the World Trade Organization’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS).

The GATS defines the conditions of entry and temporary stay in a country for business purposes, but the stay is always limited in time and is not meant to be for immigration and long term residence purposes. Equal treatment provisions, recognition of professional qualifications and social security coordination are also not part of this framework.

However, third country nationals who register as a company in an EU member state will be treated, as an EU legal person, in the same way as EU nationals.

Free Trade and Association Agreements

The rights of service providers included in the GATS can be expanded in free trade agreements (FTAs). The EU, for example, has covered in some FTAs investors and trainees, or the right for certain categories to be accompanied by spouses. But FTAs do not cover general immigration measures as these are not related to trade. So an EU-UK free trade deal will not cover citizens’ rights. This is why in its resolution about the future relation with the UK, the European parliament has proposed to negotiate an ‘association agreement’.

Association agreements, like the one between the EU and Turkey, allow covering broader aspects of the relationship, including social security coordination, aggregation and export of pensions and equal treatment in the labour market. All this, however, will have to be negotiated and will depend on the conditions the UK will offer to EU nationals after Brexit.

Claudia Delpero © all rights reserved.

Photo: Former border Pourtalet (Portalet in Spanish) between France and Spain. © European Union, 2011, Source: EC – Audiovisual Service, by Johanna Leguerre.