UK same-sex unions to face hurdles in some EU countries from 2021

Same-sex unions registered in the United Kingdom from January 2021 may not be recognised in some EU countries as a result of the UK withdrawal from the European Union.

Divorce proceedings starting after December 31st 2020 may also face hurdles as they will fall outside the scope of EU law.

The new legal situation affects UK-based LGBT couples who move or plan to move to EU countries where same-sex unions are not permitted.

It could have implications for tax, inheritance and children matters, according to experts at law firm Kingsley Napley LLP in London. There could be obstacles moving with the partner, and difficulties could emerge in the event of a future divorce or separation.

EU family law

In the UK, civil partnerships of same-sex persons are allowed since 2005 and marriages since 2014. Such unions have so far been recognised across the European Union.

But as the country has left the bloc and the post-Brexit transition ends on December 31st 2020, from next year EU family law will no longer apply to the UK.

Unions and separations registered in Britain before the end of the transition will continue to be recognised in the EU, as their legal value is carried forward by the withdrawal agreement.

Divorce proceedings that have started but have not finished before the end of the transition period will continue under EU regulations too.

But new unions or separations (irrespective of when the marriage took place) after December 31st 2020 will not benefit from EU law.

Instead, the international recognition of marriages, divorces, separations, children and maintenance orders will be governed by the Hague Conventions on Private International Law. These conventions do not cover civil partnerships and have not been signed by all EU countries.

Alternatively, as things stand, each EU country will apply national legislation on a unilateral basis, even if the UK will continue to recognise unions celebrated in other EU states.

Several EU countries do not permit same-sex partnerships.

As a consequence, UK-based LGBT couples may face obstacles moving there in the future. For instance, if one of the partners moves for work, the other may not be able to claim residence rights as a spouse.

In addition, “in countries where a same-sex marriage or a civil union is not considered legally valid, for the purpose of divorce or dissolution, it will be as if that union never existed, leaving partners without the financial claims they would ordinarily have on divorce,” Stacey Nevin, Senior Associate at Kingsley Napley, told Europe Street.

EU law and LGBT rights

Even though the EU does not have competency to legislate on family rights, LGBT unions are affected by a number of EU laws.

The Treaty of Amsterdam, signed in 1997, introduced an EU-wide ban on “discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation”.

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, adopted in 2000 and enforced in 2009, strengthened the concept by binding the EU and its members to make laws in line with that principle.

Any discrimination based on any ground such as sex, race, colour, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, age or sexual orientation shall be prohibited.

Article 21(1) of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights

Free movement rules gave EU citizens the right to reside in other EU countries with their family and the Court of Justice of the European Union has ruled that “family members” include same-sex spouses.

This principle applies also in EU countries that do not recognise same-sex unions, if at least one partner is an EU citizen and the marriage was celebrated in the EU. But civil partnerships are recognised only where national legislation allows them.

Another piece of law relevant to LGBT couples is the Brussels IIa regulation, which ensures the recognition and enforcement of matrimonial and parental judgments across EU states.

As family law has not been a priority in the post-Brexit negotiations and a bespoke agreement on these matters is unlikely, the UK is expected to be outside the scope of all these rules from January 1st 2021.

UK-EU families involved in separations after the Brexit transition may therefore have to deal with more complex legal procedures, difficulties in the recognition of court decisions across borders, and delays that may impact children.

For same-sex couples, there will be one additional layer of problems: depending on the country in question, their unions might not be recognised at all.

International conventions

Outside EU law, some EU countries are signatories to the Hague Conventions on Private International Law, which address some of the matters now covered under EU law.

The 1978 Convention on the Recognition of the Validity of Marriages, which is understood to cover same-sex marriages, has been signed in the EU by Finland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Portugal.

Twelve EU member states (Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and Sweden) are party to the 1970 Hague Convention on Divorce Recognition.

Decisions on maintenance are covered by the 2007 Hague Maintenance Convention, which has been signed by all EU countries, except for Denmark.

These decisions can also be recognized under the 2007 Lugano Convention on judgments in civil and commercial matters. The EU is a signatory and, following Brexit, the UK has applied to join as an independent party. But the EU could oppose the UK entry or the UK could join months after the end of the Brexit transition, leaving a legal gap in the meantime.

The UK has so far only agreed with Norway to continue the mutual recognition of civil court judgments in the absence of a deal at EU level.

27 different rules

For all cases not covered by the Hague Conventions, national rules will apply, making things even more complicated.

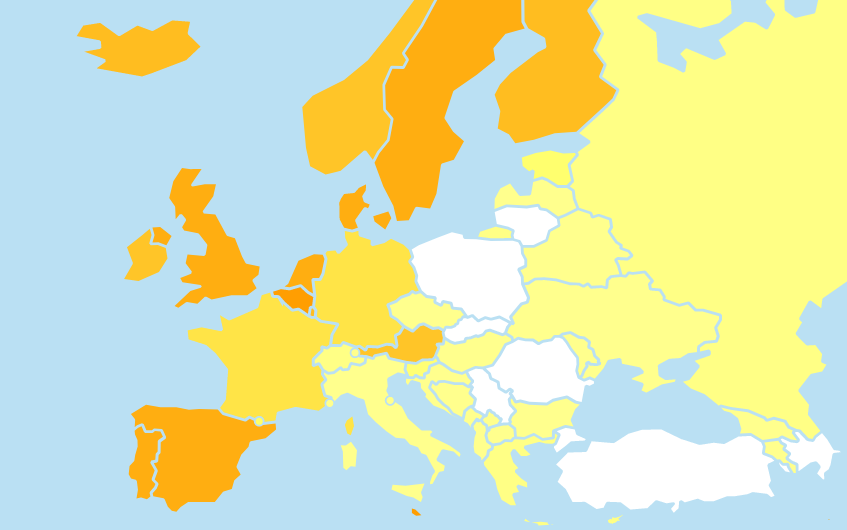

Countries where the situation could be problematic are Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovakia and Romania. These states have no form of recognition of same-sex unions and lack legislation on registered partnerships, Arpi Avetisyan, Senior Litigation Officer at the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) in Brussels, told Europe Street.

In addition, same-sex marriages are forbidden in Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, and Slovenia, although these countries (Bulgaria excluded) allow civil partnerships.

“The consequences for EU-UK same-sex marriages celebrated in the UK as of January 1st 2021 are very uncertain at the moment,” Arpi Avetisyan said.

“With the UK leaving the EU, marriages celebrated in the UK would fall outside the EU and national immigration rules will apply unless there’s a special agreement. It’s imperative that decision-makers clarify on this as soon as possible,” she continued.

“In countries that are not signatories to the Hague Conventions and that have formal constitutional bans on same-sex marriages, we are losing the path we can follow to recognise same-sex unions in the context of divorce or dissolution. There’s a real question mark there, especially for civil partnerships, which are not dealt with by the 1970 Hague Convention,” Stacey Nevin said.

“My concern is that we have so many international families now, and those living in the UK may decide to move to or back to another country within the EU, such as their home country or their partners’, without knowing that there is potentially a legal gap for the status of their relationship,” she continued.

“In the event of a future divorce, they may only come to realise this when it’s too late. It is really important that people check the domestic position before they move, but unless a couple are already considering a divorce or thinking about a nuptial agreement, this is unlikely to be something they would think to do,” she added.

The situation in the UK

In the United Kingdom, the government has published guidance clarifying that national legislation “broadly replicates” EU rules on family law. The UK will continue to recognise marriages, civil partnerships and divorces contracted in other EU member states, including court judgments.

But EU spouses of British citizens will be subject to tough immigration rules instead of benefiting from EU’s free movement when they join their partners in Britain.

A report by the University of Bristol has also warned about a possible wider erosion of rights.

With the departure from the EU, the UK has removed from its legal system the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, “the only legally binding international human rights document that expressly protects against discrimination on the ground of sexual orientation,” the authors say.

The UK parliament could therefore pass less protective legislation and the UK’s LGBT community will no longer have the EU Court as an arbitrator to resolve disputes.

The report also argues that with the UK withdrawal, the EU has lost a “broadly LGBT-supportive member” and this could “harm progress” on advancing LGBT rights across Europe in the long term.

On November 12th, 2020, the European Commission presented the first-ever EU strategy for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, non-binary, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) equality. The strategy aims to fight discrimination and hate crimes, bring forward the legislation on the mutual recognition of parenthood across borders, and explore measures to support the mutual recognition of same-gender partnership in the EU.

Claudia Delpero © all rights reserved.

This article was first published on November 8 2020 and was updated on November 15 with the UK-Norway agreement and the European Commission LGBT equality strategy. Image by Julie Rose from Pixabay.

Europe Street News is an online magazine covering citizens’ rights in Europe. We are fully independent and we are committed to providing factual, accurate and reliable information. We believe citizens’ rights are at the core of democracy and information about these topics should be accessible to all. This is why our website and newsletter are available for free. Please consider making a contribution so we can continue and expand our coverage.