If you really want to go… Germany and Brexit

“Please don’t go”

The 11 June 2016 issue of the leading German news magazine, Der Spiegel, was extraordinary. On the cover it bore a Union Jack and a plea: “Bitte geht nicht – warum wir die Britten brauchen”. To make sure that the other side of the channel also got the message it was repeated in English: “Please don’t go – why Germany needs the British”. The Brexit-related articles were all bilingual. The cover price in pounds was slashed and the cover story read much like a love letter to British and their “culture and talent for being cool”.

The Financial Times’ reaction was dismissive; it disqualified the appeal as an unusual attempt to sway public opinion ahead of the Brexit referendum. The reaction of the The Times was harsher: the title page read “Germany’s EU threat to Britain”, referring to Spiegel’s interview with the German finance minister. When asked about Britain’s chances of leaving the EU but not the Single Market, Wolfgang Schaueble, in an eerie early echo of what became Theresa May’s favourite slogan, had said “Out is out”.

This journalistic episode may seem trivial, but it reflects on key aspects of Germany’s relationship with the British and their desire to leave the EU. Many in Germany feel closer to the UK than to other European countries. Moreover, they are well aware that the UK is an important economic partner but that it has often been a difficult political partner, frequently asking for and obtaining special treatment (to use the German colloquial term, “Extra-Wurst” – a special sausage). Nevertheless, the prevailing view was that the British would choose to remain in the EU not only because of a well-understood common interest, but also because of narrow self-interest. Instead, on 24 June, they decided to go and in the process probably ask for a very big Extra-Wurst.

Initial German reactions to the Brexit decision

In Germany, the Brexit vote divided decision makers into two camps. In the first camp were those – like Vice-Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel, head of the SPD and member of the grand collision – who exclaimed that it was “a bad day for Europe” but also that it constituted a chance for a new start for the EU. Germany should play a more active role in shaping a Union that is closer to the concerns of people. In other words, the focus should be on deepening integration (where necessary), preserving the union of the 27, and minimising political fallout from Brexit negotiations on other EU members. Prolonged divorce proceedings and special deals with the UK would not be in the interest of the EU.

In the second camp were those, like Chancellor Merkel, who called for remaining calm, not rushing to conclusions, and giving the UK time to build a new government and make up their mind on how to approach the imminent divorce. In contrast to the first camp, they thought that the lesson was that the direction of “ever closer union” was being rejected (not only in the UK) and that this was not the time for further integration. But this camp was also keenly aware of the potential chain reactions that might be ignited by concessions to Britain and has always declared that if Britain wished to maintain membership of the internal market, then it would have to accept free movement of labour, paying into the EU budget and observing current and future Single Market regulations. The German government was also firm in stating that there would be no pre-negotiations before Article 50 was triggered (which obviously would have weakened the position of the EU), and this position was shared across the EU27. Thus official and public Brexit discussions were put on halt until the UK had time to regroup.

After some hesitation the British prime minster has now made two significant announcements: she has set a date for the formal start of negotiations (promised to trigger Article 50 in the first quarter of 2017), and she has declared that regaining control over immigration is non-negotiable. This raises two questions. First, is the UK really so different in terms of immigration? Second, is there any scope for a compromise on free mobility?

Is the UK disproportionally affected by immigration from the EU?

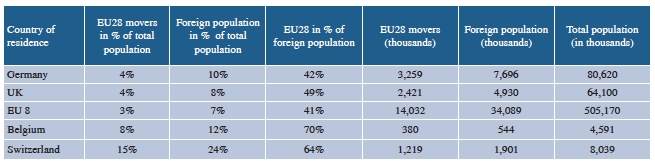

Table 1 shows that the answer to the first question is no. Out of a total population of 64 million, 2.4 million EU citizens live in the UK, that is 4%. They make about half of the total foreign population of the UK. These shares look very similar for Germany – 4% of the resident population (3.2 million) moved from other EU28 states, and the total foreign population is somewhat higher than in the UK. Both countries are very close to the EU28 averages. Therefore, there seems to be little ground for claiming a special situation in the UK.

In fact, the share of EU28 movers in the resident population in Belgium, for instance, is almost double the UK figure. And Switzerland, where movers from the EU28 make up about 15% of the population, would also have better grounds for claiming to be disproportionally affected by immigration into its labour market.

Table 1 Shares of EU28 and non-EU migrants

Note: Shares of EU28 movers and foreign population in total population, and absolute numbers (in thousands)

Source: Canetti et al. (2014), Tables 2 and 3; own calculations.

Table 1 shows stocks, but how about flows? Has the UK recently been flooded by workers from the EU (and EFTA)? While the UK has been highly attractive for recent movers of working age, so too has Germany (Figure 1). In both countries, the largest group of new movers has been from Poland, followed by Romania. It is worth restating that labour migration has predominantly been into employment. In fact, the employment rate of newcomers from the EU is typically higher than the employment rate of the resident populations, and the UK is no exception here (Canetti 2014, p. 21-22) Rather, Germany is the exception – EU newcomers to the country have slightly lower employment rates than nationals. In addition, the recent inflow of refugees from the Middle East has largely been concentrated in Germny. Based on numbers, it would appear difficult to explain to Germans (and to other EU members) why the UK should receive special treatment.

Figure 1: New EU28/EFTA movers of working age

Note: New EU28/EFTA movers are defined as EU or EFTA citizens of working age (15-64) who have been living in the UK or Germany for up to three years as of 2013.

Source: Canetti et. al (2014), Figure 8.

Can there be a compromise on free labour mobility?

On the British side, there is certainly the hope that in the end there will be a deal preserving almost full access to the Sngle Market, including passporting rights, while regaining the freedom to limit labour mobility.

On the face of it, free labour mobility may seem less important than the other three freedoms of movement, namely of goods, services and capital. After all, until recently the free movement of labour in the EU was partially restricted at least for the recent accession countries. After accession, a phased seven-year transition process allows other EU member states to apply limits to workers from the new member. During the last phase (years five to seven after accession), such restrictions may only be applied in case of serious disturbances in their labour market and after having notified the European Commission. Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU in 2007, and while some of the other EU countries granted free movement for labour immediately, others used the full transitional period. But by the end of 2013, these transitional arrangements were terminated and full labour mobility extended to Bulgaria and Romania. At present, there remain only some restrictions for workers from Croatia, which joined the EU on 1 July 2013 (Canetta et al. 2014). Such transition arrangements where only meant to give labour markets time to adjust to new entrants, to increase flexibility and smooth the path to full integration. They were not meant to be long-run solutions.

Nevertheless, one idea might be to simply extend the phase III accession regime indefinitely and grant countries the right to restrict labour mobility in the case of serious disturbances in their labour market. Pisani-Ferry et al. (2016) suggest that temporary restrictions of labour mobility might be an acceptable price to pay for sustaining deep economic integration with the UK (and possibly other countries on the outer rim).1

However, for the EU the costs of compromising on labour mobility may be very large. This is certainly the case for the Eurozone – full labour mobility is one of the preconditions for optimality of a common currency and a key adjustment mechanism for asymmetric shocks. One of the main arguments for the US being a more robust currency area than the Eurozone was the strong response of labour mobility to negative employment shocks within the US. Newer evidence, however, suggests that after the Global Crisis this is no longer true – labur mobility in response to unemployment has been higher in Europe than in the US. Jauer et al. (2014) estimate that in Europe, up to about a quarter of any asymmetric labour market shock was absorbed by migration within a year. Admitting restrictions on labour mobility would thus severely weaken the architecture of the common currency. This cannot be in the interest of Germany or of present and prospective Eurozone partners. Rather, it is in their common interest to share a robust common currency and immunise against shocks, both foreign and homemade.

Looking beyond the common currency area, the cost of compromising on labour mobility could also be very high. Presumably, restrictions would operate with quotas that would be selective based on country of origin (and possibly other criteria, such as education and qualifications). If these were admissible inside the EU, they would create first- and second-class European citizens, which could lead to constant acrimony between members. It would certainly serve as a force for further disintegration and undermine key promises of membership of the European Union – namely, prosperity and opportunity. The corrosive effect of a compromise with the UK might not be limited to the economic realm, since it could open the door for nationalist parties everywhere to also demand special treatment on all sorts of issues. This is the last thing the EU needs.

What is Germany’s self-interest?

The imminent Brexit negotiations have the potential to give rise to toxic disputes within the EU27. This would be the case if individual countries seek to gain market shares in special sectors, or to pursue short-term political victories at the expense of others. Germany’s enlightened self-interest cannot be confined to short-term cost-benefit calculus for specific goods or sectoral relative advantages. In the long run, Germany’s prosperity is inseparable from the success of Europe and the Eurozone. As the bloc’s largest economy, it has great impact but is also highly exposed to Europe. Thus its priority has to be to preserve the EU and the Eurozone, and to avoid corrosive, possibly divisive or even destructive compromises with a country that wants to leave.

Beatrice Weder di Mauro, Economic Policy and International Macroeconomics Professor, Gutenberg University Mainz; CEPR Research Fellow

This column first appeared as a chapter in the VoxEU eBook “What To Do With the UK? EU perspectives on Brexit”, available to download here, and was reproduced on VoxEU website.

Photo: Brandeburg gate, Berlin, by Drrcs15 (own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.