Sweden tops European countries for expulsion of British citizens since Brexit

The debate around Brexit has focused on ending free movement of people from the European Union to the UK. The reality is that also British citizens no longer benefit of free movement in the EU, and the consequences are becoming visible.

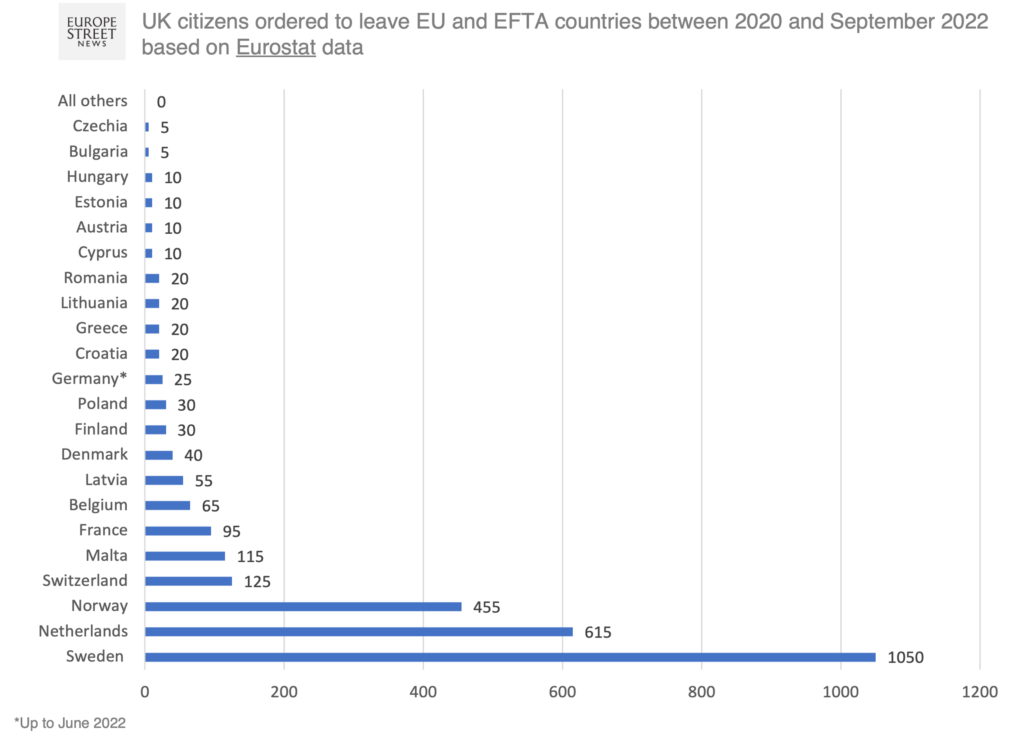

Data published in December by the EU statistical office, Eurostat, show that about 2,250 UK citizens were ordered to leave EU countries between 2020 and September 2022. The number increases to 2,830 when adding Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Switzerland, which are not part of the EU but apply free movement rules.

Information about the reasons why these Britons were ordered to leave is not available, so it is not possible to know how many living in the EU before Brexit were affected. Citizens’ rights campaigners fear there might have been problems with the implementation of the EU-UK EU withdrawal agreement.

It is also not possible to compare with past data. Eurostat does not have such information for UK citizens before 2020 because Britons were not considered third-country nationals.

Ordered to leave

Eurostat data on non-EU citizens ordered to leave include people found to be illegally present in an EU member state who are subject to an administrative or judicial decision imposing them to depart. This could be for a variety of reasons, from not meeting residency requirements to having committed crimes.

More than a million non-EU citizens were ordered to leave EU countries between 2020 and September 2022, the latest statistics show. Of these, some 2,250 were British.

The data reveal major differences in the approach taken by EU member states.

Sweden and the Netherlands

While France was responsible for the highest proportion of leave orders to non-EU citizens in 2021 (37%), it is Sweden and the Netherlands that have taken the toughest stance towards Brits.

Sweden was responsible for 1,050 leave orders to British citizens between 2020 and September 2022, with 590 between July and September 2021 alone. In those three months Sweden also imposed 110 young Britons below the age of 18 to leave.

The Netherlands follows with 615 order to leave to UK nationals since Brexit. The Dutch immigration agency IND, however, told Europe Street that even after a leave order, a person can apply for a residence permit or appeal a negative decision without leaving the country.

The IND said some 70 Britons were granted a residence permit under the withdrawal agreement after having received an order to leave.

Norway and Switzerland

Norway and Switzerland, which are not part of the EU and have separate Brexit agreements with the UK, issued 455 and 125 departure orders to UK citizens respectively, according to Eurostat data.

Malta followed with 115; France 95; Belgium 65, Latvia 55; Denmark 40; Finland and Poland 30; Germany (up to June 2022) 25; Croatia, Greece, Lithuania and Romania 20; Austria, Cyprus, Estonia and Hungary 10; Bulgaria and the Czech Republic 5.

Spain, Italy and all other countries reported zero expulsions.

Overall, UK citizens were almost 10% of people ordered to leave Malta. The share was above 2% in Sweden, the Netherlands and Latvia, while it was below 1% in all other countries.

In line with data for other nationalities, the majority of leave orders concerned men (1,560). 195 also affected young people below the age of 18, with Sweden topping the list again (135), followed by the Netherlands (20) and Germany (5), according to available information.

‘Returns’

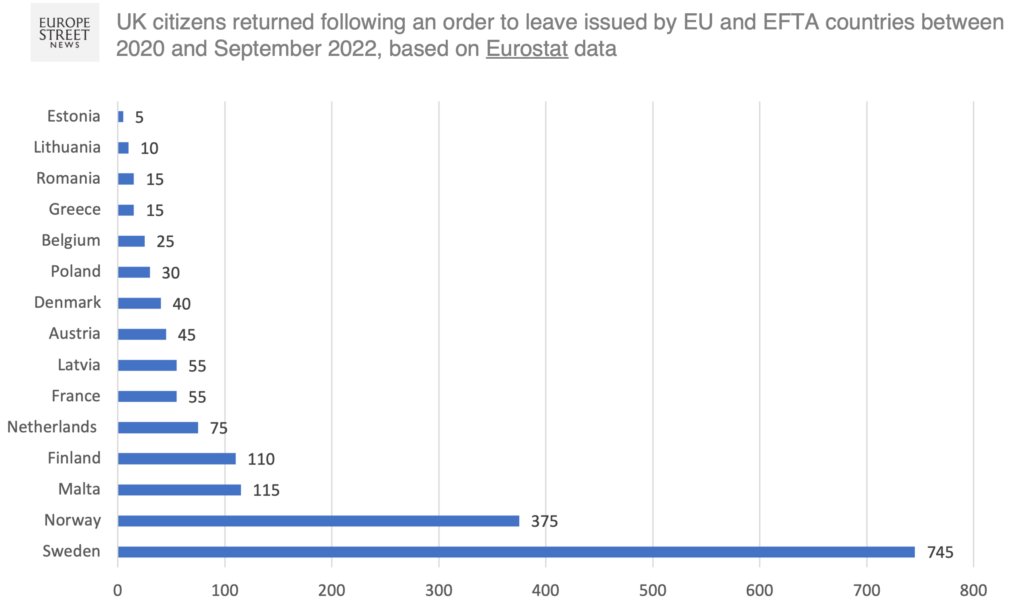

Data about ‘returns’ cover non-EU citizens who had actually to leave the territory of an EU member state following an order to leave.

Although there are gaps for some countries, Eurostat data show that 1,340 UK citizens were returned from EU member states from 2020 until September 2022. The number increases to 1,715 when counting Norway too.

Sweden was again responsible for the biggest number (745), followed by Norway (375), Malta (115), Finland (110), the Netherlands (75), France and Latvia (55), Austria (45), Denmark (40), Poland (30), Belgium (25), Greece (15), Romania (15), Lithuania (10) and Estonia (5).

The vast majority were forced returns. 320 were voluntary assisted returns, whereby UK citizens received administrative, logistical and/or financial support to leave (280 from Sweden, 30 from Denmark, 10 from Austria).

The difference between leave orders and returns can be due to persons leaving independently or regularising their situation.

In Denmark, for instance, there have been cases of individuals refused residence rights under the withdrawal agreement who could stay as ‘family members’ of EU nationals, according to citizens’ rights groups.

Lack of data

The UK left the European Union on 31 January 2020 and free movement with EU countries ended on 31 December 2020, following the post-Brexit transition period.

The withdrawal agreement secured the residence rights of Britons who had moved to the EU – and of EU citizens who had moved to the UK – before 31 December 2020. 13 EU countries and Norway required British citizens to apply for a new residence status (like the UK asked from EU citizens). The other 14 requested Britons to simply register or exchange documents.

Eurostat data do not make a distinction between Britons with rights protected under the withdrawal agreement and those who moved to EU countries after Brexit. Most countries reporting expulsions, however, had adopted a ‘constitutive’ system requesting Britons to apply to remain.

“The orders to leave figures are worrying as we don’t have the data to dig deeper into the reasons why and whether they included people covered by the withdrawal agreement,” Jane Golding, Co-Founder of the British in Europe coalition told Europe Street.

“Not surprisingly, Sweden is top of the list, as we do know that, statistically, the percentage of refusals of status in Sweden is far higher than in equivalent countries – and the numbers ordered to leave correspond fairly closely to refusals of status under the withdrawal agreement. The number in the Netherlands is more surprising. But if we consider the starting point in the negotiations – both sides said that citizens’ rights were the number one priority and nobody would be deported – that seems to have been quietly forgotten by both sides,” she added.

Golding said “the key story here is that we do not have enough data” to confirm whether the majority of people covered by these orders to leave were beneficiaries of the withdrawal agreement and “whether this means that there are problems with its implementation, especially in Sweden”.

Debbie Williams of the group Brexpats Hear our Voice said: “I’d like to see more transparency on these issues to be honest, as how do we know if the withdrawal agreement is failing people if we don’t know the detail?”

Michaela Benson, Professor of Public Sociology at Lancaster University and expert on migration, citizenship and identity, said this is “a reminder that since Brexit, British citizens no longer enjoy freedom of movement”.

“Anyone newly arriving or who did not meet the deadlines for applying for status under the terms of the withdrawal agreement, is now considered as a third country national and subject to domestic immigration controls in the EU-26 member states [the EU countries except for Ireland],” she argued.

Illegally present

When it comes to immigration law enforcement, Eurostat also collects statistical information from national authorities about non-EU citizens found to be illegally present and refused entry at the EU external borders. These data are currently available only up to 2021 and information for some member states is incomplete.

Non-EU nationals are considered illegally present under national immigration law if they have been found to have entered the country unlawfully, for instance by avoiding immigration controls or using a fraudulent document, if they overstayed their visa terms or permission to stay or if they have taken unauthorised employment.

Of the 681,200 non-EU citizens found to be illegally present in the EU in 2021, only 590 (less than 1%) were British, according to available data, which however is incomplete. Some 110 cases were due to overstays, 90 to illegal entry and 210 for “other reasons”.

Refused entry

Refused entry at the EU external borders can be due to not fulfilling entry conditions, such as having a valid passport or the right visa.

Looking at the data for 2021, a period when strict Covid-19 rules were in place, 139,000 non-EU citizens were refused entry into the EU. Of these, 4,470 (3.2%) were British.

France was responsible for more than half, 2,610. The Netherlands refused entry to 995 Brits, Switzerland 250; Germany 220; Bulgaria 125, Denmark 100; Belgium 85, Italy 70, Croatia 65, the Czech Republic 35, Sweden 30, Greece 25, Latvia and Slovakia 20, Cyprus and Poland 15, Malta and Portugal 10, Hungary 5.

More up-to-date and complete information is expected from Eurostat in May.

Claudia Delpero, Europe Street News © all rights reserved

A preview of these data was published on 4 January in cooperation with The Local. This article was updated on 12 February 2022 with more information about the Netherlands.

Photo by Martino Pietropoli on Unsplash

Europe Street News is a news service on EU citizenship rights. We are fully independent and we are committed to providing factual, accurate and reliable information. As citizens’ rights are at the core of democracy, our website and newsletter are free to read. Please consider making a contribution so we can continue and expand our coverage. Thank you!