From employment tribunal to food banks: workers’ rights thwarted by pandemic

Marcel lives in a cramped, three-bedroom house in the outskirts of London with nine other Romanians. Together with seven of his housemates, he used to work in a local carwash, scrubbing and hosing around for 10 hours a day, 6 days a week. It was hand wrenching, back straining labour, paid barely half the minimum wage – no more than £900-£1200 per month. But it was work and it brought the sense of normalcy that comes with being able to look after oneself.

At the end of March, all seven men were abruptly let go. They were not legally registered as employees, so they were left with little room for discussion. Having quickly exhausted their savings and with their rent payment looming closer, they contacted us at the Work Rights Centre.

“Ma’am, we can’t pay rent this Sunday!” was one of the first things they said. It was a cry for help, the first in a series that we have received with increasing frequency in the following weeks, as the pandemic that has brought the country to a halt has disproportionately threatened the livelihoods of those already working in precarious positions.

An emergency in every way

As a charitable organisation fighting for employment justice in the UK since 2016, especially with EU workers, we are no strangers to exploitative work. Before the pandemic, our service providers and volunteers in London and Manchester spent most days dealing with cases of non-payment and abuse, where unscrupulous bosses preyed on vulnerable staff.

A significant proportion of our clients are engaged in work arrangements with a low degree of formality. Around a third of the clients do not have a written confirmation of payment, whether in the form of a payslip or an invoice for self-employed workers.

While this is not illegal, the absence of written terms makes it harder to build a case, especially in disputes over non-payment. Even without such documentation, our charity helps workers determine their status and understand how their rights have been breached, following every step in the journey to justice.

But a large gap remains between winning a claim at the Employment Tribunal and the money reaching our clients. Because of that, 47% of our beneficiaries do not actually resolve their employment issue, but gain another job. This became almost impossible during the pandemic.

In need of immediate assistance

At the start of the lockdown, our team grabbed their laptops, locked up the office and took casework home. But something else changed. The Covid-19 pandemic created a new emergency in our beneficiaries’ lives, as many were made redundant, struggled to find work, or on the contrary, were required to return to unsafe workplaces.

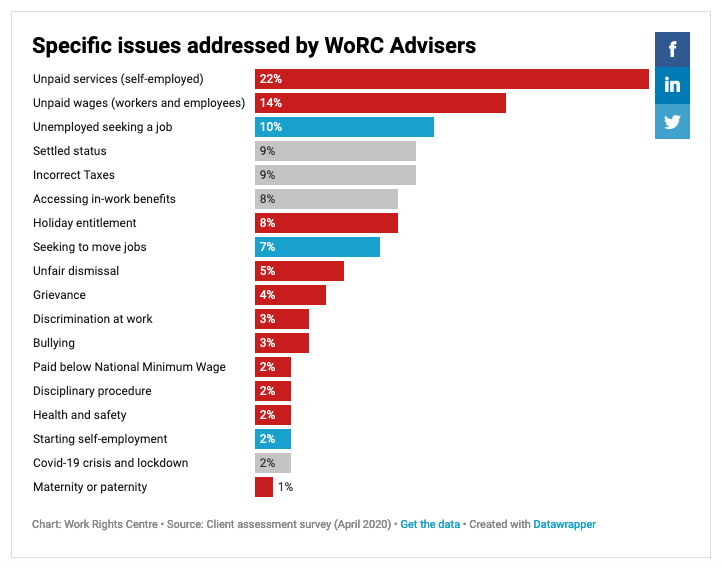

Over the phone, email, or social media, many people like Marcel reached out for immediate assistance with food, living costs and, increasingly, mental health issues. Concerned workers of many nationalities have been calling us to enquire about the possibility to access benefits, such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (usually referred to as furlough scheme for employees), the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (33% of our beneficiaries were self-employed in the first quarter of 2020) or Universal Credit, a government benefit aiming to support those who find themselves jobless, on a low income or unable to work.

Many of our beneficiaries virtually have no power to persuade their employers to furlough them. That is, furlough is a possibility, not a right, leaving workers’ security during the pandemic at the discretion of employers. Listening to several cases, there is a growing concern amongst our advisers that some employers are also abusing the scheme by claiming that their workers are on furlough while asking them to work, and retrospectively paying them only 80% of their wages instead of the full amount.

We have also encountered cases where workers who needed to return to their occupation were not provided with personal protective equipment (PPE) and were instead required to buy these materials themselves and cover the costs.

In the lives of these individuals, the coronavirus gains another deadly dimension as many have been left without food for their families and facing evictions from their homes. A few months ago, people like Marcel could pick up a new job while old abuses were being brought to justice, now the big injustices fade before the urgency of seeing livelihood under threat.

A protection deficit

Ever since the end of March, our advisers and volunteers have found themselves in a balancing act between securing livelihoods in the short-term, and standing up for employment justice in the long term. “Everything is interlinked”, explains Lora, one of our expert service providers. Precarious jobs leave many of our beneficiaries unable to save.

Whether abruptly dismissed or struggling to find work, the few savings set aside are quickly used up, leaving many unable to afford their living costs such as rent or providing food for their families. In turn, their informal work patterns make it harder to claim the rights to which workers are entitled, leading to lengthy battles against fraudulent employers and many workers being dragged back into precarious work.

There are also concerns that EU nationals who haven’t secured their residence status in the UK yet may face barriers when applying for government support.

Across the board, these situations need urgent solutions. But the urgency imposed by this crisis is shining a light onto the rips in the safety net meant to support those in precarious work.

For thousands of people who lack the privilege of working from home, the main options are to wait, brave the work they can find in one of the key sectors, or apply for Universal Credit, the only solution available to thousands of people dismissed under lockdown.

Our advisers helped the eight workers apply for Universal Credit, navigating the platform, opening a bank account when needed, and translating the complexity of life into a form. Seven were successful in their applications. One of them got a job in a supermarket and helped the others while the applications were being considered.

Yet, it takes five weeks between the moment a case is approved and the first payment. To fill this gap and help workers put food on the table, we built a referral system for local food banks over the space of a couple of days and scoured the London boroughs for other sources of support.

While catering to these short-term needs, we continue to fight for workers’ rights as abusive practices have not gone away. This meant offering Marcel and his colleagues to draft statements for an HMRC investigation into the fraudulent tax practices of their employer. However, the seven men decided against making a claim to the Employment Tribunal and asking for compensation for their rights as workers, even though they could be entitled to a hefty compensation. They feared they might need to return to the carwash if they were unable to find work due to the pandemic. In fact, two of the seven men have already returned there.

Even before the Covid-19 crisis, the scenario where workers return to their precarious jobs was common, as many lack the digital and language skills to find a job elsewhere. And especially in times of crisis, unscrupulous employers capitalise on workers’ anxieties for financial gain. All that is left for us is to carefully monitor the situation as written terms of employment are being negotiated, and support our clients looking for other jobs.

Deeply entrenched inequalities

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the deeply entrenched inequalities present in our society. Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) worker were worst struck, women were disproportionately burdened with household work and caring responsibilities, refugees were stuck in squalid camps where social distancing is impossible. Our beneficiaries are no exception, and we fear that this protection deficit will not disappear once the lockdown is lifted.

A study by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre has shown that it is migrant workers who might suffer the worst effects of the economic downturn, as they are more likely to be employed on temporary contracts, earn lower wages and carry out tasks that are not compatible with teleworking.

The current pandemic is also exposing the failures of a system meant to protect the many workers like Marcel, as informal work hinders their access to the employment rights they are entitled to.

As men and women are called back to work, we continue to monitor their safety and carve out a space for justice dealing with cases like Marcel’s that may now start with an immediate need for livelihood support and end with a hearing at the Employment Tribunal.

By Ana-Maria Cîrstea, Research Assistant, in cooperation with Dr Dora-Olivia Vicol, Director of the Work Rights Centre. Work Rights Centre © all rights reserved.

The Work Rights Centre is a charity registered in England and Wales dedicated to employment justice. Every week caseworkers in London and Manchester help people fight unscrupulous employers and access their lawful entitlements. The Work Rights Centre advice is free, confidential, and available in a range of languages. The organisation’s mission is driven by the conviction that everyone has the right to work that is fair, safe, and that pays.

Photo: people queuing outside a store, by Dati Bendo, © European Union, 2020. Source: EC – Audiovisual Service.