Diary of a survivor: exclusive memories of an Anglo-Italian on the Arandora Star

Born Giorgio Enrico Scola in Sanremo, Italy, in 1916, my father died George Henry Scola in Reading, England, in 2006. He became a British citizen in the 1950s and was later awarded an Imperial Service Medal for his long years of work in the civil service.

But in 1940, aged 23 and studying architecture, he was arrested and detained by the British authorities as an ‘enemy alien’.

Following the Nazi invasion of France and the evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk in May 1940, Britain feared invasion, and Germans and Italians in the UK were accused in the media of being a ‘5th column’.

About 28,000 people, mainly Germans and Austrians, including many Jewish refugees, were arrested and held in makeshift camps. 4,000 were Italians.

Giorgio was one of 1,500 Italian, Austrian and German internees put on a converted cruise ship to be deported to Canada. Nazis and Fascists were mixed with refugees – Jews, anti-nazis and anti-fascists – as well as hotel and restaurant workers not involved in politics.

The day after setting off from Liverpool, the Arandora Star, painted battle grey with a very visible gun emplacement but no red cross indicating that it carried civilians, was torpedoed by a German U-boat. It sunk with the loss of over 800 people, half of them Italians.

Miraculously, my father survived, pulled from the water into a lifeboat and eventually rescued up by a Canadian destroyer. Taken back to near Glasgow, my father writes in his diary:

“Bare-footed and ill-clad most of us 254 odd Italian survivors are paraded out on the cobbled quay in the cold morning – nearly 60 of our number go to hospital. With people looking on, we are marched under guard through the streets like a column of tramps and are taken to a barracks (a converted factory). I am desperately hungry and after waiting an hour or two in a crowded hall we all get a slice of corned beef on bread and hot tea. I am very cold until blankets are provided. We get an inadequate tea and supper which we have to eat with our hands. We have to sleep terribly crowded together on the wooden floor without mattresses.”

Within 10 days, and to his horror, he and most survivors of the Arandora Star, and others including refugees, were put on another ship, the Dunera, and set sail for an unknown destination.

His diary recalls:

“Before going up the gangway we are one by one roughly manhandled and not only our belongings, but our person is minutely searched, and the contents of our pockets ruthlessly emptied. Any word of protest is greeted by a blow”.

Two days later my father recounts:

“Some time after breakfast, we are horrified to hear a loud explosion, quickly followed by another – our nerves already on edge with the previous experience behind us. One and all make a rush for the door at the head of the stairs, which is found to be locked – there are shouts and cries but all to no avail until two or three men get hold of a piece of wood and attempt to batter down some wooden panels. The air is stifling, and I am almost crushed – everyone fears the worse: that we are sinking and that we won’t have a chance to escape. The ram breaks through and as one man is starting to get through to the deck, several soldiers rush up pointing fixed bayonets through the opening and tell us to calm down as everything is alright – none of us believe them and refuse to go down, at which one threatens to fire.”

In fact, the Dunera narrowly escaped suffering the same fate as the Arandora Star, but the torpedoes missed and exploded at a harmless distance from the ship.

After that, “we begin to settle down to the unbearably monotonous routine” writes my father, although the ship was overcrowded, had inadequate lavatory facilities, and the “plain robbery” by the military guards continued. Within a week there were “strong rumours that we are going to Australia”, and this was confirmed some time later.

My father was one of about 600 to disembark in Melbourne in September 1940. He went on to spend almost five years in camps in Australia. His diary notes that after leaving the Dunera “I sleep properly for the first time for weeks”.

Conditions in the camps were decent and internees were well-treated by the Australians.

“To my delight, our meals were ample and varied including eggs, rabbit, pastry, risotto and minestrone. The Melbourne daily paper which we saw on occasions gave exaggerated accounts of our ‘dangerous past’ as either fifth columnists or ‘agents’ captured at Dunkirk! During the voyage we were also supposed to have enjoyed ourselves with concerts and hours of sun-bathing on the decks! My own observations are very different to these.”

Three British officers were court-martialled for their treatment of the internees on the Dunera.

My father was not given permission to return to Britain until December 1944. He obtained passage in March 1945, and on arriving in the UK was held in a camp on the Isle of Man for four more months before being allowed to return to his mother and the home he had been taken from more than five years previously. He then contributed to Britain’s war recovery using his architectural studies to survey buildings for reconstruction.

My father loved Britain and never expressed any resentment about his treatment. He would say he was safer and better fed than many who remained in England.

He was deported and held so long because he was a member of the Italian Fascist Party, a party whose leader was admired and praised by some in Britain before the war, but many internees were not members of the party, including refugees and migrants who drowned with the Arandora Star.

While far from the worst horrors of World War II, the internment and needless death of refugees and workers who were simply trying to make better lives for themselves is a little known chapter in Britain’s history. It should make us reflect on whether refugees should be treated more humanely today and whether we shouldn’t be more insistent on the value of European co-operation over nationalism.

Julian Scola

Julian Scola, the son of Giorgio Enrico Scola, lives and works in Brussels

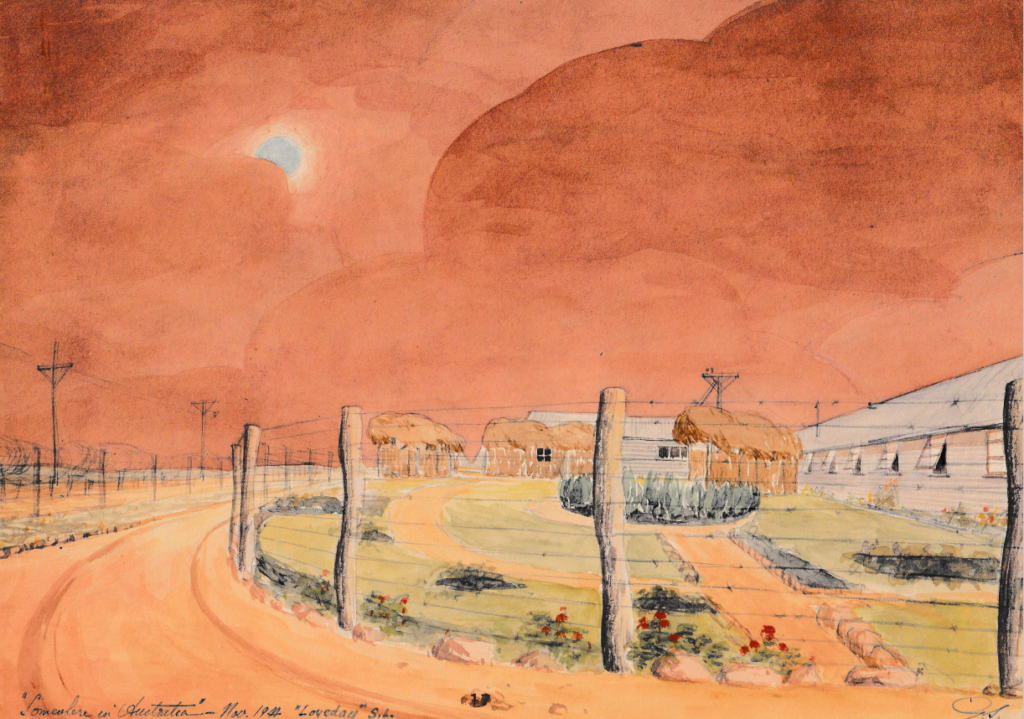

‘12,000 miles behind barbed wire’, Giorgio Scola’s diary illustrated with his watercolours and sketches, can be downloaded here. Further information are available from InternmentDiary@gmail.com.

For more on the Arandora Star tragedy see https://arandorastar.online/

Document and images courtesy of Julian Scola. The top photo was taken in Tatura Camp in January 1943. Giorgio Enrico Scola is in the front row on the far left (wearing a beret).

Europe Street News is a news service on the European Union and citizens’ rights. We are fully independent and we are committed to providing factual, accurate and reliable information. As citizens’ rights are at the core of democracy, our website and newsletter are free to read. Please consider making a contribution of your choice using this link or the menu below so we can continue and expand our coverage. We are always happy to hear your suggestions and ideas for improvement. Thank you!