Who came up with the idea of EU citizenship? Spain

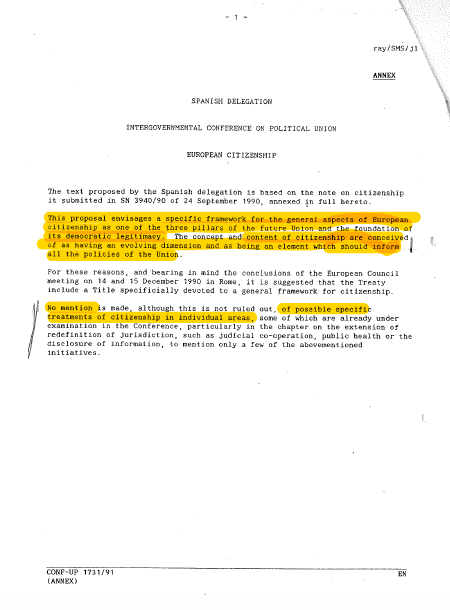

It was Spain, rather than the EU, which proposed in 1990 to include EU citizenship in the mandate for negotiations on the Maastricht Treaty. And that proposal went in the direction of a transformative and dynamic citizenship in the making. It was seen as a counterweight to economic and monetary union and a way of strengthening territorial cohesion in the context of a European political union.

The approach by the government of Felipe Gonzalez was put forward in short papers sent to the EU Council and obtained by us under the access to documents regulation.

At the time the proposals from Spain caused surprise in the inner circles of the EU, which tend to concentrate on rights and their enforcement, rather than citizenship. Was this some kind of bargaining chip? What were the Spanish really after with this proposal or was it genuinely idealistic? Only people in Madrid with a long memory could answer those questions.

For in the run up to the Maastricht Treaty the proposals by Spain were quickly watered down in less than a month of negotiations and without any wider debate. In those days intergovernmental conferences on Treaty reform were just that and strictly secret.

There are therefore unanswered questions and a disparity between the original input for the proposal to create Union citizenship and the outcome in what are now articles 18-25 of the Treaty on the functioning of the EU.

The visionary and open-minded nature of those early Spanish proposals on EU citizenship stand in some contrast to the current legalistic discourse on preserving the integrity of national citizenship. With citizenship so much in the forefront of the political crisis in Spain would it not be logical for civil society and political forces to revisit what remains – despite the defects – the most original contribution of that country to the EU? Since the Maastricht Treaty there have been no substantial proposals to develop EU citizenship.

If we turn to the EU, similar arguments in favour of new initiatives on European citizenship can also be made.

There are sound grounds for the EU not to be drawn in any crisis which concerns the internal territorial integrity of a member state or how the relationship between the central government and regions are organised, especially given the absence of any single model in a disparate Union.

Even in the world of non-profit European associations great care is taken to avoid quarrels within a country being imported to poison what is often a fragile cooperative effort. In addition there are cast iron legal reasons for non-interference.

European citizenship and Catalonia

Carles Puigdemont came to Brussels in autumn of 2017 exercising his right to free movement as a European citizen, but what happens next in response the European arrest warrant issued by the Spanish authorities is in the hands of the Belgian judiciary. Nevertheless, the EU is coming in for widespread criticism by its refusal to say anything. It could point for example to subsidiarity to explain why it cannot interfere directly, whilst nevertheless sending messages to the politicians in Madrid and Barcelona: the EU is a legal Union but in realty can only operate on the basis of permanent dialogue and political bargaining.

In modern Europe there is also a strange sense of anachronism about both sides in the conflict between state power and repression on the one hand and 19th century nationalistic romanticism on the other. Barcelona is a city with as strong a European as a regional and linguistic identity. The EU institutions could say more, but all the signs are that debate on Europe is at a low level in Spain.

The more powerful message which could come from the EU is about Union citizenship. In a more globalised world, something more than just one’s national citizenship is needed. For mobile families with parents of different nationality freedom of movement and rights to equal treatment associated with union citizenship often serve to avoid having to make difficult choices about the nationality of the children. This transnational citizenship could also alleviate tensions of the kind surfacing so dramatically in Spain. For citizens with opposing views of the future of Spanish citizenship there is at least a shared citizenship, beyond their own territory.

Many people will argue that Union citizenship is too weak to play such a role in considerations of citizenship. The Court of Justice of the EU has shown the opposite and that as a “fundamental status” Union citizenship as such can be invoked to challenge national rules as discriminatory and a violation of European rights in such sensitive areas as access to social benefits, educational systems or rights to family reunion. The Court shows that national measures can sometimes discriminate unnecessarily against citizens coming from neighbouring countries but also that such measures are sometimes justified. This is a useful counter argument to calls for nationalism and “taking back control” in favour of mutual access across borders of neighbouring countries and shared rather than exclusive identity.

A political definition of citizenship

There needs however to be an attempt to frame EU citizenship politically and not just in legal terms. If beyond the nation state, there is no common citizenship and only other national governments where do those go for whom their own citizenship is not enough? They might join populist and nationalistic movements or seek more autonomy within their own region below rather than beyond the national level.

One lesson therefore for the EU and Member States, although powerless in the Catalan crisis, is that is in their interests to consider new ways to develop Union citizenship because it is additional to and does not compete with national citizenship.

Tony Venables, Founder of the ECIT (European Citizens’ Rights, Involvement and Trust) Foundation, Brussels.

This article was originally published on the ECIT Foundation website. Photo courtesy Pixabay.