London wants more autonomy

Few cities in the world embrace openness and celebrate diversity like London. A blend of peoples and cultures, the British capital for decades has been considered the city of opportunities, where hard work could be rewarded no matter where you were from.

But Brexit is opening some cracks in this world of possibilities. In London’s financial centre, banks are preparing to move staff to other European cities, to keep operating without barriers in the EU market. Two agencies of the European Union – for banking and medicines – will move too once the UK leaves the bloc. Restrictions to the arrival of people from EU countries are likely to hit sectors such as hospitality, construction, education and technology.

Loved and hated by the Brits, will the British capital maintain its international influence after the UK leaves the European Union, or will it succumb to its detractors, stricken by the combined competition of Dublin, Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Paris, Madrid and Milan?

The Centre for London, an organisation created in 2011 to deal with the challenges of the city, and the Institute for Policy Research at the University of Bath, have analysed the Brexit risks “that disproportionately affect” the British capital. They came up with a solution: giving London more autonomy.

Risking everything

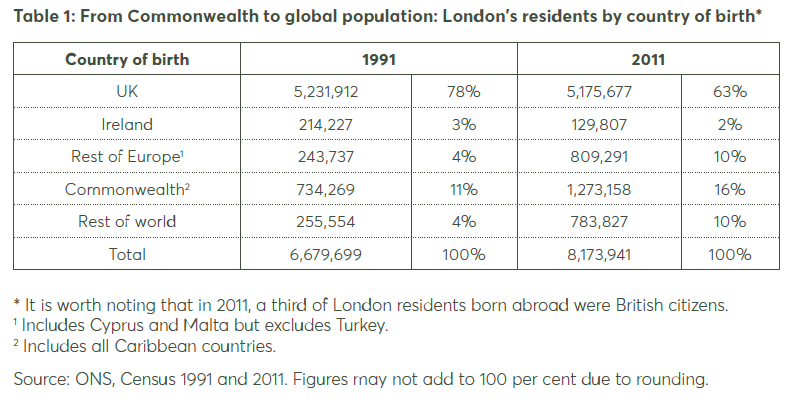

There’s a lot at stake, says the report “Open City: London after Brexit”. With 13% of residents from other EU countries, London is more reliant on EU workers than any other British region. A third of EU citizens based in the UK live in the capital. 82% of those working in London occupy middle- to high-skilled roles (against 73% in the rest of the UK). A quarter to a third of jobs in sectors like construction and catering are held by people from the European Economic Area (EEA). 33,000 of London’s 360,000 students are from EU countries. Also, there are constant exchanges with the rest of Europe, as every year between 10,000 and 50,000 EEA-born Londoners move to the continent.

Source: Centre for London report.

The diversity is not surprising in London’s international context. The city is the first UK exporter region for services and the second for goods, after the South East. Over the years, a favourable taxation has appealed foreign businesses and investors and today, 40% of the 250 top global companies have their global or regional headquarters in the city. Support and legal services, engineering, architecture, media, creative industries, technology start-ups and international charities benefit of the same environment and infrastructures.

It’s the so-called “agglomeration effect”, the power to attract knowledge-intensive firms, jobs and workers that, operating together, keep improving skills, develop innovation and increase productivity.

All that glitters is not gold

But not everything is great, far from it. London suffers from all the diseases of global cities: high cost of living, growing inequality, congestion, air pollution. It has also specific problems of its own. Housing is on top of them. House prices increased by 67% in the past five years, five times faster than wages, making purchases and rents unaffordable especially for younger people.

Unemployment is also higher than other English regions and is above the national average for women, young people, workers over 50 and minorities. Women with children are less likely to be working in London (61.4% employment rate compared to 72.1% in the rest of the UK) due to a childcare system that does not consider longer working hours, commutes and overall affordability. 37% of London’s children grow up in poverty, against a UK average of 26%.

Adding to this mix the impacts of a bad managed Brexit could be “catastrophic,” argues the report.

Childcare, special visas, tax autonomy

Which solutions then? The Centre for London says the city should be given more autonomy in three key areas: childcare, migration and taxation. After all, “nearly 70% of London’s revenue comes from central government, compared to 26% in New York, 16.3% in Paris, and 5.6% in Tokyo.”

London could design more flexible and better targeted childcare and early education, encouraging mothers to take up jobs.

A regionally managed migration system, with quotas agreed with the government, would allow to maintain easy exchanges with the rest of Europe. “A first step must be the safeguarding of the position of EEA nationals already living here,” says the report. After Brexit, there could be work visas for one to six years with long-term residents having the opportunity to apply to stay permanently. European citizens could also be given a year to look for employment or start-up opportunities, with fast-track work permits for those who succeed. Easy access could also be ensured for young people and students who want to stay after graduation.

“The government should agree reciprocal ‘Young European’ working tourist visas for under-30s, with fast-tracked work permit applications permitted at the end of that period,” says the report. “These people not only help meet London’s labour needs, but also develop ideas for start-ups, for cultural events, for new social movements.”

On the problem of housing, London wants the ability to reform property taxes (council tax, stamp duty and land tax), as these often privilege the wealthiest. Devolved taxes could then be used to solve the housing and infrastructure crises.

Finally, the Centre of London says there should be transitional arrangements with the EU. Ideally the UK should provisionally stay in the European Economic Area, while negotiating the details of the EU exit. This should be clarified as soon as possible to avoid an exodus from London, as people and companies try to manage uncertainty.

In support of the report, a coalition of businesses, institutions, academic organisations and politicians, including the Mayor of London, have signed an open letter to Brexit Secretary David Davis.

Claudia Delpero © all rights reserved.

Photo via Pixabay.